Greek historian Diodorus said that diagnosis was made by the position of the patient in bed. (6, page 25) Medical historian Thomas Bradford said treatment was standard and based on the symptoms. (6, page 25) (1, page 6)

Bradford said:

While preparing the ingredients, might site the following incantation: (3, page 23)The Egyptians paid strict attention to dietetic rules; they thought that the majority of diseases were caused by indigestion, and excess in eating. They practiced abstinence and used emetics. They had a considerable knowledge of Materia Medica (the pharmacopoeia) and used many drugs in the cure of the sick. They were somewhat skilled in operative surgery. They practiced castration, lithotomy and amputations

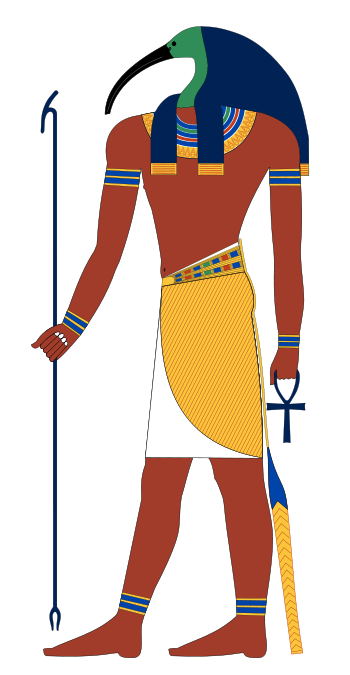

"May Isis heal me, as she healed Horns of all the ills inflicted upon him when Set slew his father, Osiris. 0 Isis, thou great enchantress, free me, deliver me from all evil, bad and horrible things, from the god and goddess of evil, from the cod and goddess of sickness, and from the unclean demon who presses upon me, as thou didst loose and free thy son Horus"As you can see, the medical profession among "the ancient Egyptians hold the honor of being the first people to cultivate medicine as a science," and that this "medicine was closely associated with the mythology of Egypt." (2, page 1)

Surely we might look at Egyptian medicine, as well as medicine of any ancient society, and think to ourselves: this is quackery. Yet these ancient societies probably benefited more from the magic of incantations and prayers, or by the gentle touch of a palm on the shoulder, than from any other form of medicine. As noted by Henry Sigerist in his 1951 book, "A History of Medicine: Primitive and Archaic Medicine: (13, page 280-1)

The oral rite was all important. The correct choice of words to frighten a spirit, to enlist the help of the gods, the intonation probably also in which a spell was recited or sung, this all must have had a profound effect upon the patient. We know the power of suggestion and know how highly responsive religious individuals are to such rites. I should not be astonished if the sorcerer with his spells had had as better results in many cases than the physician with his drugs. Magician and priest were able to put the sick in a frame of mind in which the healing power of the organism could do its work under the best conditions. They gave him peace and confidence and helped him to readjust to the world from which disease had torn him.(13, page 280)Sigerist also said:

The manual rites performed in the course of an incantation appear in infinite variety from the simplest to the most elaborate and complicated. The rite may have consisted of nothing but putting one's hand on the patient, the classical gesture of protection so familiar to us from the Bible. After having exorcised a demon the magician said: 'My hands are on this child, and the hands of Isis are on him, as she puts her hands on her son Horus.' Or the magician held his seal over the child and such as seal was obviously a powerful fetish: 'My hand is on thee and my seal is thy protection' (13, page 281)There may have come a day when, said Sigerist, "drugs were prepared and given without incantation and this was the moment when magic and medicine separated, when physicians and magician-priest became different individuals." (13, page 280)

Yet the priest of the ancient world, whether using magic words or herbal remedies, would have known of the power of suggestion, and perhaps, just perhaps, never ceased to use the power of magical words, amulets, talismans and gesticulations.

References:

- Sandwich, Fleming Mant, "The medical diseases of Egypt, part I," 1905, London

- Bradford, Thomas Lindsley, "Quiz questions on the history of medicine: form the lectures of Thomas Lindsley Bradford, M.D," 1898, Philadelphia

- Baas, Johann Herman, author, Henry Ebenezer Sanderson, translator, "Outlines of the history of medicine and the medical profession," 1889, New York

- Renouard, Pierce Victor, "History of Medicine: From it's origin to the 19th century," 1856, Cincinnati, Moore, Wistach, Keys and Co., page 26, chapter 1, "Medicine of the Antique Nation."

- Garrison, Fielding Hudon, "An introduction to the history of medicine," 1922, Philadelphia and London, W.B. Saunders Company

- Dunglison, Robley, author, Richard James Dunglison, editor, "History of Medicine from the earliest ages to the commencement of the nineteenth century," 1872, Philadelphia, Lindsay and Blakiston

- Hamilton, William, "The history of medicine, surgery, and anatomy, from the creation of the world to the commencement of the nineteenth century," 1831, volume I, London, Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley

- Puschmann, Theodor, translated by Evan H. Hare, "A history of medical education from teh most remote to the most recdent times," 1891, London, H.K. Lewis

- Puschman, Theodor, translated by Evan H. Hare, "A history of medical education from the most remote to the most recent times," 1891, London, H.K. Lewis

- Prioreschi, Plinio, "A History of Medicine," Volume 1: Primitive and Ancient Medicine," 1991, Edwin Mellen Press, Chapter IV: Egyhptian Medicine, page 257. Reference noted by author is as follows: Homer, "Ocyssey, IV, 229-232, Translation by A.T. Murray.

- Wilder, Aleander, "History of Medicine," 1901, Maine, New England eclectic Publishing

- Osler, William, "Evolution of Modern Medicine: a series of lectures at Yale University to the Silliman Foundation in April 1913, 1921", New haven, Yale University Press

- Sigerist, Henry E, "A History of Medicine: Primitive and Archaic Medicine," volume I, 1951, New York, Oxford University Press

RT Cave on Twitter